Don't ask, don't tell

| Don't ask, don't tell | |

|---|---|

President Bill Clinton announcing new policy regarding homosexual servicemembers in July 1993 | |

| Planned | Department of Defense Directive 1304.26 |

| Planned by | Clinton administration |

| Date | February 28, 1994 – September 20, 2011 |

| Executed by | Les Aspin |

| Barring of openly gay, bisexual, and lesbian persons from the United States Armed Forces | |

"Don't ask, don't tell" (DADT) was the official United States policy on military service of non-heterosexual people. Instituted during the Clinton administration, the policy was issued under Department of Defense Directive 1304.26 on December 21, 1993, and was in effect from February 28, 1994, until September 20, 2011.[1] The policy prohibited military personnel from discriminating against or harassing closeted homosexual or bisexual service members or applicants, while barring openly gay, lesbian, or bisexual persons from military service. This relaxation of legal restrictions on service by gays and lesbians in the armed forces was mandated by Public Law 103–160 (Title 10 of the United States Code §654), which was signed November 30, 1993.[2] The policy prohibited people who "demonstrate a propensity or intent to engage in homosexual acts" from serving in the armed forces of the United States, because their presence "would create an unacceptable risk to the high standards of morale, good order and discipline, and unit cohesion that are the essence of military capability".[3]

The act prohibited any non-heterosexual person from disclosing their sexual orientation or from speaking about any same-sex relationships, including marriages or other familial attributes, while serving in the United States armed forces. The act specified that service members who disclose that they are homosexual or engage in homosexual conduct should be separated (discharged) except when a service member's conduct was "for the purpose of avoiding or terminating military service" or when it "would not be in the best interest of the armed forces".[4] Since DADT ended in 2011, persons who are openly homosexual and bisexual have been able to serve.[5]

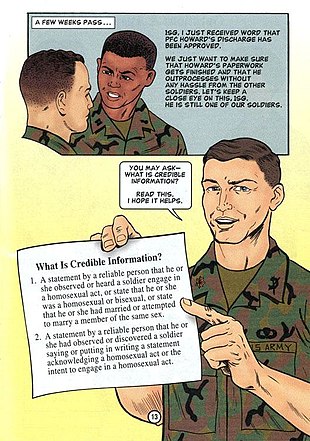

The "don't ask" section of the DADT policy specified that superiors should not initiate an investigation of a service member's orientation without witnessing disallowed behaviors. However, evidence of homosexual behavior deemed credible could be used to initiate an investigation. Unauthorized investigations and harassment of suspected servicemen and women led to an expansion of the policy to "don't ask, don't tell, don't pursue, don't harass".[6]

Beginning in the early 2000s, several legal challenges to DADT were filed, and legislation to repeal DADT was enacted in December 2010, specifying that the policy would remain in place until the President, the Secretary of Defense, and the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff certified that repeal would not harm military readiness, followed by a 60-day waiting period.[7] A July 6, 2011, ruling from a federal appeals court barred further enforcement of the U.S. military's ban on openly gay service members.[8] President Barack Obama, Secretary of Defense Leon Panetta, and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Admiral Mike Mullen sent that certification to Congress on July 22, 2011, which set the end of DADT to September 20, 2011.[9]

Even with DADT repealed, the legal definition of marriage as being one man and one woman under the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA) meant that, although same-sex partners could get married, their marriage was not recognized by the federal government. This barred partners from access to the same benefits afforded to heterosexual couples such as base access, health care, and United States military pay, including family separation allowance and Basic Allowance for Housing with dependents.[10] The Department of Defense attempted to open some of the benefits that were not restricted by DOMA,[11] but the Supreme Court decision in United States v. Windsor (2013) made these efforts unnecessary.[12]

Background

[edit]

Engaging in homosexual activity had been grounds for discharge from the American military since the Revolutionary War. Policies based on sexual orientation appeared as the United States prepared to enter World War II. When the military added psychiatric screening to its induction process, it included homosexuality as a disqualifying trait, then seen as a form of psychopathology. When the army issued revised mobilization regulations in 1942, it distinguished "homosexual" recruits from "normal" recruits for the first time.[13] Before the buildup to the war, gay service members were court-martialed, imprisoned, and dishonorably discharged; but in wartime, commanding officers found it difficult to convene court-martial boards of commissioned officers and the administrative blue discharge became the military's standard method for handling gay and lesbian personnel. In 1944, a new policy directive decreed that homosexuals were to be committed to military hospitals, examined by psychiatrists, and discharged under Regulation 615–360, section 8.[14]

In 1947, blue discharges were discontinued and two new classifications were created: "general" and "undesirable". Under such a system, a serviceman or woman found to be gay but who had not committed any sexual acts while in service would tend to receive an undesirable discharge. Those found guilty of engaging in sexual conduct were usually dishonorably discharged.[15] A 1957 U.S. Navy study known as the Crittenden Report dismissed the charge that homosexuals constitute a security risk, but nonetheless did not advocate for an end to anti-gay discrimination in the navy on the basis that "The service should not move ahead of civilian society nor attempt to set substantially different standards in attitude or action with respect to homosexual offenders." It remained secret until 1976.[16] Fannie Mae Clackum was the first service member to successfully appeal such a discharge, winning eight years of back pay from the US Court of Claims in 1960.[17]

From the 1950s through the Vietnam War, some notable gay service members avoided discharges despite pre-screening efforts, and when personnel shortages occurred, homosexuals were allowed to serve.[18]

The gay and lesbian rights movement in the 1970s and 1980s raised the issue by publicizing several noteworthy dismissals of gay service members. Air Force TSgt Leonard Matlovich, the first service member to purposely out himself to challenge the ban, appeared on the cover of Time in 1975.[19] In 1982 the Department of Defense issued a policy stating that, "Homosexuality is incompatible with military service." It cited the military's need "to maintain discipline, good order, and morale" and "to prevent breaches of security".[20] In 1988, in response to a campaign against lesbians at the Marines' Parris Island Depot, activists launched the Gay and Lesbian Military Freedom Project (MFP) to advocate for an end to the exclusion of gays and lesbians from the armed forces.[21] In 1989, reports commissioned by the Personnel Security Research and Education Center (PERSEREC), an arm of the Pentagon, were discovered in the process of Joseph Steffan's lawsuit fighting his forced resignation from the U.S. Naval Academy. One report said that "having a same-gender or an opposite-gender orientation is unrelated to job performance in the same way as is being left- or right-handed."[22] Other lawsuits fighting discharges highlighted the service record of service members like Tracy Thorne and Margarethe (Grethe) Cammermeyer. The MFP began lobbying Congress in 1990, and in 1991 Senator Brock Adams (D-Washington) and Rep. Barbara Boxer introduced the Military Freedom Act, legislation to end the ban completely. Adams and Rep. Pat Schroeder (D-Colorado) re-introduced it the next year.[23] In July 1991, Secretary of Defense Dick Cheney, in the context of the outing of his press aide Pete Williams, dismissed the idea that gays posed a security risk as "a bit of an old chestnut" in testimony before the House Budget Committee.[24] In response to his comment, several major newspapers endorsed ending the ban, including USA Today, the Los Angeles Times, and the Detroit Free Press.[25] In June 1992, the General Accounting Office released a report that members of Congress had requested two years earlier estimating the costs associated with the ban on gays and lesbians in the military at $27 million annually.[26]

During the 1992 U.S. presidential election campaign, the civil rights of gays and lesbians, particularly their open service in the military, attracted some press attention,[27] and all candidates for the Democratic presidential nomination supported ending the ban on military service by gays and lesbians,[28] but the Republicans did not make a political issue of that position.[29] In an August cover letter to all his senior officers, General Carl Mundy Jr., Commandant of the Marine Corps, praised a position paper authored by a Marine Corps chaplain that said that "In the unique, intensely close environment of the military, homosexual conduct can threaten the lives, including the physical (e.g. AIDS) and psychological well-being of others". Mundy called it "extremely insightful" and said it offered "a sound basis for discussion of the issue".[30] The murder of gay U.S. Navy petty officer Allen R. Schindler Jr. on October 27, 1992, brought calls from advocates of allowing open service by gays and lesbians for prompt action from the incoming Clinton administration.[31]

Origin

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| LGBTQ rights |

|---|

|

| Lesbian ∙ Gay ∙ Bisexual ∙ Transgender ∙ Queer |

|

|

The policy was introduced as a compromise measure in 1993 by President Bill Clinton who campaigned in 1992 on the promise to allow all citizens to serve in the military regardless of sexual orientation.[32] Commander Craig Quigley, a Navy spokesman, expressed the opposition of many in the military at the time when he said, "Homosexuals are notoriously promiscuous" and that in shared shower situations, heterosexuals would have an "uncomfortable feeling of someone watching".[33]

During the 1993 policy debate, the National Defense Research Institute prepared a study for the Office of the Secretary of Defense published as Sexual Orientation and U.S. Military Personnel Policy: Options and Assessment. It concluded that "circumstances could exist under which the ban on homosexuals could be lifted with little or no adverse consequences for recruitment and retention" if the policy were implemented with care, principally because many factors contribute to individual enlistment and re-enlistment decisions.[34] On May 5, 1993, Gregory M. Herek, associate research psychologist at the University of California at Davis and an authority on public attitudes toward lesbians and gay men, testified before the House Armed Services Committee on behalf of several professional associations. He stated, "The research data show that there is nothing about lesbians and gay men that makes them inherently unfit for military service, and there is nothing about heterosexuals that makes them inherently unable to work and live with gay people in close quarters." Herek added, "The assumption that heterosexuals cannot overcome their prejudices toward gay people is a mistaken one."[35]

In Congress, Democratic Senator Sam Nunn of Georgia and Chair of the Senate Armed Services Committee led the contingent that favored maintaining the absolute ban on gays. Reformers were led by Democratic Congressman Barney Frank of Massachusetts, who favored modification (but ultimately voted for the defense authorization bill with the gay ban language), and 1964 Republican presidential nominee Barry Goldwater, a former Senator and a retired Major General,[36] who argued on behalf of allowing service by open gays and lesbians but was not allowed to appear before the Committee by Nunn. In a June 1993 Washington Post opinion piece, Goldwater wrote: "You don't have to be straight to shoot straight".[37] The White House was also reportedly upset when LGBT activist David Mixner openly described Nunn as an "old-fashioned bigot" for opposing Clinton's plan to lift the ban on gays in the military.[38]

Congress rushed to enact the existing gay ban policy into federal law, outflanking Clinton's planned repeal effort. Clinton called for legislation to overturn the ban, but encountered intense opposition from the Joint Chiefs of Staff, members of Congress, and portions of the public. DADT emerged as a compromise policy.[39] Congress included text in the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 1994 (passed in 1993) requiring the military to abide by regulations essentially identical to the 1982 absolute ban policy.[40] The Clinton administration on December 21, 1993,[41] issued Defense Directive 1304.26, which directed that military applicants were not to be asked about their sexual orientation.[40] This policy is now known as "Don't Ask, Don't Tell". The phrase was coined by Charles Moskos, a military sociologist.

In accordance with the December 21, 1993, Department of Defense Directive 1332.14,[42] it was legal policy (10 U.S.C. § 654)[43] that homosexuality was incompatible with military service and that persons who engaged in homosexual acts or stated that they are homosexual or bisexual were to be discharged.[32][40] The Uniform Code of Military Justice, passed by Congress in 1950 and signed by President Harry S Truman, established the policies and procedures for discharging service members.[44]

The full name of the policy at the time was "Don't Ask, Don't Tell, Don't Pursue". The "Don't Ask" provision mandated that military or appointed officials not ask about or require members to reveal their sexual orientation. The "Don't Tell" stated that a member may be discharged for claiming to be a homosexual or bisexual or making a statement indicating a tendency towards or intent to engage in homosexual activities. The "Don't Pursue" established what was minimally required for an investigation to be initiated. A "Don't Harass" provision was added to the policy later. It ensured that the military would not allow harassment or violence against service members for any reason.[39]

The Servicemembers Legal Defense Network was founded in 1993 to advocate an end to discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation in the U.S. Armed Forces.[45]

Court challenges

[edit]DADT was upheld by five federal Courts of Appeal.[46] The Supreme Court, in Rumsfeld v. Forum for Academic and Institutional Rights, Inc. (2006), unanimously held that the federal government could constitutionally withhold funding from universities, no matter what their nondiscrimination policies might be, for refusing to give military recruiters access to school resources. An association of law schools had argued that allowing military recruiting at their institutions compromised their ability to exercise their free speech rights in opposition to discrimination based on sexual orientation as represented by DADT.[47]

McVeigh v. Cohen

[edit]In January 1998, Senior Chief Petty Officer Timothy R. McVeigh (not to be confused with convicted Oklahoma City bomber, Timothy J. McVeigh) won a preliminary injunction from a U.S. district court that prevented his discharge from the U.S. Navy for "homosexual conduct" after 17 years of service. His lawsuit did not challenge the DADT policy but asked the court to hold the military accountable for adhering to the policy's particulars. The Navy had investigated McVeigh's sexual orientation based on his AOL email account name and user profile. District Judge Stanley Sporkin ruled in McVeigh v. Cohen that the Navy had violated its own DADT guidelines: "Suggestions of sexual orientation in a private, anonymous email account did not give the Navy a sufficient reason to investigate to determine whether to commence discharge proceedings."[48] He called the Navy's investigation "a search and destroy mission" against McVeigh. The case also attracted attention because a navy paralegal had misrepresented himself when querying AOL for information about McVeigh's account. Frank Rich linked the two issues: "McVeigh is as clear-cut a victim of a witch hunt as could be imagined, and that witch hunt could expand exponentially if the military wants to add on-line fishing to its invasion of service members' privacy."[49] AOL apologized to McVeigh and paid him damages. McVeigh reached a settlement with the Navy that paid his legal expenses and allowed him to retire with full benefits in July. The New York Times called Sporkin's ruling "a victory for gay rights, with implications for the millions of people who use computer on-line services".[50]

Witt v. Department of the Air Force

[edit]In April 2006, Margaret Witt, a major in the United States Air Force who was being investigated for homosexuality, filed suit in the United States District Court for the Western District of Washington seeking declaratory and injunctive relief on the grounds that DADT violates substantive due process, the Equal Protection Clause, and procedural due process. In July 2007 the Secretary of the Air Force ordered her honorable discharge. Dismissed by the district court, the case was heard on appeal, and the Ninth Circuit issued its ruling on May 21, 2008. Its decision in Witt v. Department of the Air Force reinstated Witt's substantive-due-process and procedural-due-process claims and affirmed the dismissal of her Equal Protection claim. The Ninth Circuit, analyzing the Supreme Court decision in Lawrence v. Texas (2003), determined that DADT had to be subjected to heightened scrutiny, meaning that there must be an "important" governmental interest at issue, that DADT must "significantly" further the governmental interest, and that there can be no less intrusive way for the government to advance that interest.

The Obama administration declined to appeal, allowing a May 3, 2009, deadline to pass, leaving Witt as binding on the entire Ninth Circuit, and returning the case to the District Court.[51] On September 24, 2010, District Judge Ronald B. Leighton ruled that Witt's constitutional rights had been violated by her discharge and that she must be reinstated to the Air Force.[52]

The government filed an appeal with the Ninth Circuit on November 23, but did not attempt to have the trial court's ruling stayed pending the outcome.[53] In a settlement announced on May 10, 2011, the Air Force agreed to drop its appeal and remove Witt's discharge from her military record. She will retire with full benefits.[54]

Log Cabin Republicans v. United States of America

[edit]In 2010, a lawsuit filed in 2004 by the Log Cabin Republicans (LCR), the nation's largest Republican gay organization, went to trial.[55] Challenging the constitutionality of DADT, the plaintiffs stated that the policy violates the rights of gay military members to free speech, due process and open association. The government argued that DADT was necessary to advance a legitimate governmental interest.[56] Plaintiffs introduced statements by President Barack Obama, from prepared remarks, that DADT "doesn't contribute to our national security", "weakens our national security", and that reversal is "essential for our national security". According to plaintiffs, these statements alone satisfied their burden of proof on the due process claims.[57]

On September 9, 2010, Judge Virginia A. Phillips ruled in Log Cabin Republicans v. United States of America that the ban on service by openly gay service members was an unconstitutional violation of the First and Fifth Amendments.[58][59] On October 12, 2010, she granted an immediate worldwide injunction prohibiting the Department of Defense from enforcing the "Don't Ask Don't Tell" policy and ordered the military to suspend and discontinue any investigation or discharge, separation, or other proceedings based on it.[60][61] The Department of Justice appealed her decision and requested a stay of her injunction,[62] which Phillips denied but which the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals granted on October 20[63][64] and stayed pending appeal on November 1.[65] The U.S. Supreme Court refused to overrule the stay.[66] District Court neither anticipated questions of constitutional law nor formulated a rule broader than is required by the facts. The constitutional issues regarding DADT are well-defined, and the District Court focused specifically on the relevant inquiry of whether the statute impermissibly infringed upon substantive due process rights with regard to a protected area of individual liberty. Engaging in a careful and detailed review of the facts presented to it at trial, the District Court concluded that the Government put forward no persuasive evidence to demonstrate that the statute is a valid exercise of congressional authority to legislate in the realm of protected liberty interests. See Log Cabin, 716 F. Supp. 2d at 923. Hypothetical questions were neither presented nor answered in reaching this decision. On October 19, 2010, military recruiters were told they could accept openly gay applicants.[67] On October 20, 2010, Lt. Dan Choi, an openly gay man honorably discharged under DADT, re-enlisted in the U.S. Army.[68]

Following the passage of the Don't Ask, Don't Tell Repeal Act of 2010, the Justice Department asked the Ninth Circuit to suspend LCR's suit in light of the legislative repeal. LCR opposed the request, noting that gay personnel were still subject to discharge. On January 28, 2011, the Court denied the Justice Department's request.[69] The Obama administration responded by requesting that the policy be allowed to stay in place while they completed the process of assuring that its end would not impact combat readiness. On March 28, the LCR filed a brief asking that the court deny the administration's request.[70]

In 2011, while waiting for certification, several service members were discharged under DADT at their own insistence,[71] until July 6 when a three-judge panel of the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals re-instated Judge Phillips' injunction barring further enforcement of the U.S. military's ban on openly gay service members.[72] On July 11, the appeals court asked the DOJ to inform the court if it intended to proceed with its appeal.[73] On July 14, the Justice Department filed a motion "to avoid short-circuiting the repeal process established by Congress during the final stages of the implementation of the repeal".[74] and warning of "significant immediate harms on the government". On July 15, the Ninth Circuit restored most of the DADT policy,[74] but continued to prohibit the government from discharging or investigating openly gay personnel. Following the implementation of DADT's repeal, a panel of three judges of the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals vacated the Phillips ruling.[75]

Debate

[edit]

Following the July 1999 murder of Army Pfc. Barry Winchell, apparently motivated by anti-gay bias, President Clinton issued an executive order modifying the Uniform Code of Military Justice to permit evidence of a hate crime to be admitted during the sentencing phase of a trial.[76][77] In December, Secretary of Defense William Cohen ordered a review of DADT to determine if the policy's anti-gay harassment component was being observed.[78] When that review found anti-gay sentiments were widely expressed and tolerated in the military, the DOD adopted a new anti-harassment policy in July 2000, though its effectiveness was disputed.[76] On December 7, 1999, Hillary Clinton told an audience of gay supporters that "Gays and lesbians already serve with distinction in our nation's armed forces and should not face discrimination. Fitness to serve should be based on an individual's conduct, not their sexual orientation."[79] Later that month, retired General Carl E. Mundy Jr. defended the implementation of DADT against what he called the "politicization" of the issue by both Clintons. He cited discharge statistics for the Marines for the past five years that showed 75% were based on "voluntary admission of homosexuality" and 49% occurred during the first six months of service, when new recruits were most likely to reevaluate their decision to enlist. He also argued against any change in the policy, writing in the New York Times: "Conduct that is widely rejected by a majority of Americans can undermine the trust that is essential to creating and maintaining the sense of unity that is critical to the success of a military organization operating under the very different and difficult demands of combat."[80] The conviction of Winchell's murderer, according to the New York Times, "galvanized opposition" to DADT, an issue that had "largely vanished from public debate". Opponents of the policy focused on punishing harassment in the military rather than the policy itself, which Senator Chuck Hagel defended on December 25: "The U.S. armed forces aren't some social experiment."[81]

The principal candidates for the Democratic presidential nomination in 2000, Al Gore and Bill Bradley, both endorsed military service by open gays and lesbians, provoking opposition from high-ranking retired military officers, notably the recently retired commandant of the Marine Corps, General Charles C. Krulak. He and others objected to Gore's statement that he would use support for ending DADT as a "litmus test" when considering candidates for the Joint Chiefs of Staff.[82] The 2000 Democratic Party platform was silent on the issue,[83] while the Republican Party platform that year said: "We affirm that homosexuality is incompatible with military service."[84] Following the election of George W. Bush in 2000, observers expected him to avoid any changes to DADT, since his nominee for Secretary of State Colin Powell had participated in its creation.[85]

In February 2004, members of the British Armed Forces, Lt Rolf Kurth and Lt Cdr Craig Jones, along with Aaron Belkin, Director of the Center for the Study of Sexual Minorities in the Military met with members of Congress and spoke at the National Defense University. They spoke about their experience of the current situation in the UK. The UK lifted the gay ban on members serving in their forces in 2000.[86][87]

In July 2004, the American Psychological Association issued a statement that DADT "discriminates on the basis of sexual orientation" and that "Empirical evidence fails to show that sexual orientation is germane to any aspect of military effectiveness including unit cohesion, morale, recruitment and retention." It said that the U.S. military's track record overcoming past racial and gender discrimination demonstrated its ability to integrate groups previously excluded.[88] The Republican Party platform that year reiterated its support for the policy—"We affirm traditional military culture, and we affirm that homosexuality is incompatible with military service."[89]—while the Democratic Party maintained its silence.[90]

In February 2005, the Government Accountability Office released estimates of the cost of DADT. It reported at least $95.4 million in recruiting costs and at least $95.1 million for training replacements for the 9,488 troops discharged from 1994 through 2003, while noting that the true figures might be higher.[91] In September, as part of its campaign to demonstrate that the military allowed open homosexuals to serve when its workforce requirements were greatest, the Center for the Study of Sexual Minorities in the Military (now the Palm Center) reported that army regulations allowed the active-duty deployment of Army Reservists and National Guard troops who claim to be or who are accused of being gay. A U.S. Army Forces Command spokesperson said the regulation was intended to prevent Reservists and National Guard members from pretending to be gay to escape combat.[92][93] Advocates of ending DADT repeatedly publicized discharges of highly trained gay and lesbian personnel,[94] especially those in positions with critical shortages, including fifty-nine Arabic speakers and nine Persian speakers.[95][96] Elaine Donnelly, president of the Center for Military Readiness, later argued that the military's failure to ask about sexual orientation at recruitment was the cause of the discharges: [Y]ou could reduce this number to zero or near zero if the Department of Defense dropped Don't Ask, Don't Tell. ... We should not be training people who are not eligible to be in the Armed Forces."[97]

In February 2006, a University of California Blue Ribbon Commission that included Lawrence Korb, a former assistant defense secretary during the Reagan administration, William Perry, Secretary of Defense in the Clinton administration, and professors from the United States Military Academy released their assessment of the GAO's analysis of the cost of DADT released a year earlier. The commission report stated that the GAO did not take into account the value the military lost from the departures. They said that that total cost was closer to $363 million, including $14.3 million for "separation travel" following a service member's discharge, $17.8 million for training officers, $252.4 million for training enlistees, and $79.3 million in recruiting costs.[91]

In 2006, Soulforce, a national LGBT rights organization, organized its Right to Serve Campaign, in which gay men and lesbians in several cities attempted to enlist in the Armed Forces or National Guard.[98] Donnelly of the Center for Military Readiness stated in September: "I think the people involved here do not have the best interests of the military at heart. They never have. They are promoting an agenda to normalize homosexuality in America using the military as a battering ram to promote that broader agenda." She said that "pro-homosexual activists ... are creating media events all over the country and even internationally."[99]

In 2006, a speaking tour of gay former service members, organized by SLDN, Log Cabin Republicans, and Meehan, visited 18 colleges and universities. Patrick Guerriero, executive director of Log Cabin, thought the repeal movement was gaining "new traction" but "Ultimately", said, "we think it's going to take a Republican with strong military credentials to make a shift in the policy." Elaine Donnelly called such efforts "a big P.R. campaign" and said that "The law is there to protect good order and discipline in the military, and it's not going to change."[100]

In December 2006, Zogby International released the results of a poll of military personnel conducted in October 2006 that found that 26% favored allowing gays and lesbians to serve openly in the military, 37% were opposed, while 37% expressed no preference or were unsure. Of respondents who had experience with gay people in their unit, 6% said their presence had a positive impact on their personal morale, 66% said no impact, and 28% said negative impact. Regarding overall unit morale, 3% said positive impact, 64% no impact, and 27% negative impact.[101]

Retired Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff General John Shalikashvili[102] and former Senator and Secretary of Defense William Cohen[103] opposed the policy in January 2007: "I now believe that if gay men and lesbians served openly in the United States military, they would not undermine the efficacy of the armed forces" Shalikashvili wrote. "Our military has been stretched thin by our deployments in the Middle East, and we must welcome the service of any American who is willing and able to do the job."[104] Shalikashvili cited the recent "Zogby poll of more than 500 service members returning from Afghanistan and Iraq, three-quarters of whom said they were comfortable interacting with gay people.[105] The debate took a different turn in March when General Peter Pace, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, told the editorial board of the Chicago Tribune he supported DADT because "homosexual acts between two individuals are immoral and ... we should not condone immoral acts."[106] His remarks became, according to the Tribune, "a huge news story on radio, television and the Internet during the day and showed how sensitive the Pentagon's policy has become."[107] Senator John Warner, who backed DADT, said "I respectfully, but strongly, disagree with the chairman's view that homosexuality is immoral", and Pace expressed regret for expressing his personal views and said that DADT "does not make a judgment about the morality of individual acts."[108] Massachusetts Governor Mitt Romney, then in the early stages of his campaign for the 2008 Republican presidential nomination, defended DADT:[109]

When I first heard [the phrase], I thought it sounded silly and I just dismissed it and said, well, that can't possibly work. Well, I sure was wrong. It has worked. It's been in place now for over a decade. The military says it's working and they don't want to change it ... and they're the people closest to the front. We're in the middle of a conflict right now. I would not change it.

That summer, after U.S. Senator Larry Craig was arrested for lewd conduct in a men's restroom, conservative commentator Michael Medved argued that any liberalization of DADT would "compromise restroom integrity and security". He wrote: "The national shudder of discomfort and queasiness associated with any introduction of homosexual eroticism into public men's rooms should make us more determined than ever to resist the injection of those lurid attitudes into the even more explosive situation of the U.S. military."[110]

In November 2007, 28 retired generals and admirals urged Congress to repeal the policy, citing evidence that 65,000 gay men and women were serving in the armed forces and that there were over a million gay veterans.[104][111] On November 17, 2008, 104 retired generals and admirals signed a similar statement.[111] In December, SLDN arranged for 60 Minutes to interview Darren Manzella, an Army medic who served in Iraq after coming out to his unit.[112]

In 2008, former U.S. Senator Sam Nunn, who previously stalled efforts to lift the ban on gays serving in military when he was Chairman of the Senate Armed Forces Committee, hinted a shift from his previous political views by endorsing a new Pentagon study to examine the issue of homosexuals serving openly in the military, stating "I think [when] 15 years go by on any personnel policy, it's appropriate to take another look at it—see how it's working, ask the hard questions, hear from the military. Start with a Pentagon study."[113]

On May 4, 2008, while Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Admiral Mike Mullen addressed the graduating cadets at West Point, a cadet asked what would happen if the next administration were supportive of legislation allowing gays to serve openly. Mullen responded, "Congress, and not the military, is responsible for DADT." Previously, during his Senate confirmation hearing in 2007, Mullen told lawmakers, "I really think it is for the American people to come forward, really through this body, to both debate that policy and make changes, if that's appropriate." He went on to say, "I'd love to have Congress make its own decisions" with respect to considering repeal.[114]

In May 2009, when a committee of military law experts at the Palm Center, an anti-DADT research institute, concluded that the President could issue an Executive Order to suspend homosexual conduct discharges,[115] Obama rejected that option and said he wanted Congress to change the law.[116]

On July 5, 2009, Colin Powell told CNN that the policy was "correct for the time" but that "sixteen years have now gone by, and I think a lot has changed with respect to attitudes within our country, and therefore I think this is a policy and a law that should be reviewed." Interviewed for the same broadcast, Mullen said the policy would continue to be implemented until the law was repealed, and that his advice was to "move in a measured way. ... At a time when we're fighting two conflicts there is a great deal of pressure on our forces and their families."[117] In September, Joint Force Quarterly published an article by an Air Force colonel[118] that disputed the argument that unit cohesion is compromised by the presence of openly gay personnel.[119]

In October 2009, the Commission on Military Justice, known as the Cox Commission, repeated its 2001 recommendation that Article 125 of the Uniform Code of Military Justice, which bans sodomy, be repealed, noting that "most acts of consensual sodomy committed by consenting military personnel are not prosecuted, creating a perception that prosecution of this sexual behavior is arbitrary."[120]

In January 2010, the White House and congressional officials started work on repealing the ban by inserting language into the 2011 defense authorization bill.[121] During Obama's State of the Union Address on January 27, 2010, he said that he would work with Congress and the military to enact a repeal of the gay ban law and for the first time set a timetable for repeal.[122]

At a February 2, 2010, congressional hearing, Senator John McCain read from a letter signed by "over one thousand former general and flag officers". It said: "We firmly believe that this law, which Congress passed to protect good order, discipline and morale in the unique environment of the armed forces, deserves continued support."[123] The signature campaign had been organized by Elaine Donnelly of the Center for Military Readiness, a longtime supporter of a traditional all-male and all-heterosexual military.[124] Servicemembers United, a veterans group opposed to DADT, issued a report critical of the letter's legitimacy. They said that among those signing the letter were officers who had no knowledge of their inclusion or who had refused to be included, and even one instance of a general's widow who signed her husband's name to the letter though he had died before the survey was published. The average age of the officers whose names were listed as signing the letter was 74, the oldest was 98, and Servicemembers United noted that "only a small fraction of these officers have even served in the military during the 'Don't Ask, Don't Tell' period, much less in the 21st century military."[125]

The Center for American Progress issued a report in March 2010 that said a smooth implementation of an end to DADT required eight specified changes to the military's internal regulations.[126] On March 25, 2010, Defense Secretary Gates announced new rules mandating that only flag officers could initiate discharge proceedings and imposing more stringent rules of evidence on discharge proceedings.[127]

Repeal

[edit]The underlying justifications for DADT had been subjected to increasing suspicion and outright rejection by the early 21st century. Mounting evidence obtained from the integration efforts of foreign militaries, surveys of U.S. military personnel, and studies conducted by the DoD gave credence to the view that the presence of open homosexuals within the military would not be detrimental at all to the armed forces. A DoD study conducted at the behest of Secretary of Defense Robert Gates in 2010 supports this most.

The DoD working group conducting the study considered the impact that lifting the ban would have on unit cohesion and effectiveness, good order and discipline, and military morale. The study included a survey that revealed significant differences between respondents who believed they had served with homosexual troops and those who did not believe they had. In analyzing such data, the DoD working group concluded that it was actually generalized perceptions of homosexual troops that led to the perceived unrest that would occur without DADT. Ultimately, the study deemed the overall risk to military effectiveness of lifting the ban to be low. Citing the ability of the armed forces to adjust to the previous integration of African-Americans and women, the DoD study asserted that the United States military could adjust as had it before in history without an impending serious effect.[128]

In March 2005, Rep. Martin T. Meehan introduced the Military Readiness Enhancement Act in the House. It aimed "to amend title 10, United States Code, to enhance the readiness of the Armed Forces by replacing the current policy concerning homosexuality in the Armed Forces, referred to as 'Don't ask, don't tell,' with a policy of nondiscrimination on the basis of sexual orientation".[129] As of 2006, it had 105 Democrats and 4 Republicans as co-sponsors.[100] He introduced the bill again in 2007 and 2009.

During the 2008 U.S. presidential election campaign, Senator Barack Obama advocated a full repeal of the laws barring gays and lesbians from serving in the military.[130] Nineteen days after his election, Obama's advisers announced that plans to repeal the policy might be delayed until 2010, because Obama "first wants to confer with the Joint Chiefs of Staff and his new political appointees at the Pentagon to reach a consensus, and then present legislation to Congress".[131] As president he advocated a policy change to allow gay personnel to serve openly in the armed forces, stating that the U.S. government has spent millions of dollars replacing troops expelled from the military, including language experts fluent in Arabic, because of DADT.[132] On the eve of the National Equality March in Washington, D.C., October 10, 2009, Obama stated in a speech before the Human Rights Campaign that he would end the ban, but he offered no timetable.[133][134] Obama said in his 2010 State of the Union Address: "This year, I will work with Congress and our military to finally repeal the law that denies gay Americans the right to serve the country they love because of who they are."[135] This statement was quickly followed up by Defense Secretary Robert Gates and Joint Chiefs chairman Michael Mullen voicing their support for a repeal of DADT.[136]

Don't Ask, Don't Tell Repeal Act of 2010

[edit]

Democrats in both houses of Congress first attempted to end DADT by amending the Defense Authorization Act. On May 27, 2010, on a 234–194 vote,[137] the U.S. House of Representatives approved the Murphy amendment[138] to the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2011. It provided for repeal of the DADT policy and created a process for lifting the policy, including a U.S. Department of Defense study and certification by key officials that the change in policy would not harm military readiness followed by a waiting period of 60 days.[139][140] The amended defense bill passed the House on May 28, 2010.[141] On September 21, 2010, John McCain led a successful filibuster against the debate on the Defense Authorization Act, in which 56 Senators voted to end debate, four short of the 60 votes required.[142] Some advocates for repeal, including the Palm Center, OutServe, and Knights Out, opposed any attempt to block the passage of NDAA if it failed to include DADT repeal language. The Human Rights Campaign, the Center for American Progress, Servicemembers United and SLDN refused to concede that possibility.[143]

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) filed a lawsuit, Collins v. United States, against the Department of Defense in November 2010 seeking full compensation for those discharged under the policy.[144]

On November 30, 2010, the Joint Chiefs of Staff released the "Don't Ask, Don't Tell" Comprehensive Review Working Group (CRWG) report authored by Jeh C. Johnson, General Counsel of the Department of Defense, and Army General Carter F. Ham.[145][146] It outlined a path to the implementation of repeal of DADT.[147] The report indicated that there was a low risk of service disruptions due to repealing the ban, provided time was provided for proper implementation and training.[145][148] It included the results of a survey of 115,000 active-duty and reserve service members. Across all service branches, 30 percent thought that integrating gays into the military would have negative consequences. In the Marine Corps and combat specialties, the percentage with that negative assessment ranged from 40 to 60 percent. The CRWG also said that 69 percent of all those surveyed believed they had already worked with a gay or lesbian and of those, 92 percent reported that the impact of that person's presence was positive or neutral.[147][148] The same day, in response to the CRWG, 30 professors and scholars, most from military institutions, issued a joint statement saying that the CRWG "echoes more than 20 studies, including studies by military researchers, all of which reach the same conclusion: allowing gays and lesbians to serve openly will not harm the military ... We hope that our collective statement underscores that the debate about the evidence is now officially over".[149] The Family Research Council's president, Tony Perkins, interpreted the CRWG data differently, writing that it "reveals that 40 percent of Marines and 25 percent of the Army could leave".[150]

Gates encouraged Congress to act quickly to repeal the law so that the military could carefully adjust rather than face a court decision requiring it to lift the policy immediately.[148] The United States Senate held two days of hearings on December 2 and 3, 2010, to consider the CRWG report. Defense Secretary Robert Gates, Joint Chiefs chairman Michael Mullen urged immediate repeal.[151] The heads of the Marine Corps, Army, and Navy all advised against immediate repeal and expressed varied views on its eventual repeal.[152] Oliver North, writing in National Review the next week, said that Gates' testimony showed "a deeply misguided commitment to political correctness". He interpreted the CRWG's data as indicating a high risk that large numbers of resignations would follow the repeal of DADT. Service members, especially combat troops, he wrote, "deserve better than to be treated like lab rats in Mr. Obama's radical social experiment".[153]

On December 9, 2010, another filibuster prevented debate on the Defense Authorization Act.[154] In response to that vote, Senators Joe Lieberman and Susan Collins introduced a bill that included the policy-related portions of the Defense Authorization Act that they considered more likely to pass as a stand-alone bill.[155] It passed the House on a vote of 250 to 175 on December 15, 2010.[156] On December 18, 2010, the Senate voted to end debate on its version of the bill by a cloture vote of 63–33.[157] The final Senate vote was held later that same day, with the measure passing by a vote of 65–31.[158]

U.S. Secretary of Defense Robert Gates released a statement following the vote indicating that the planning for implementation of a policy repeal would begin right away and would continue until Gates certified that conditions were met for orderly repeal of the policy.[159] President Obama signed the repeal into law on December 22, 2010.[7]

Implementation of repeal

[edit]The repeal act established a process for ending the DADT policy. The President, the Secretary of Defense and the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff were required to certify in writing that they had reviewed the Pentagon's report on the effects of DADT repeal, that the appropriate regulations had been reviewed and drafted, and that implementation of repeal regulations "is consistent with the standards of military readiness, military effectiveness, unit cohesion, and recruiting and retention of the Armed Forces". Once certification was given, DADT would be lifted after a 60-day waiting period.[160]

Representative Duncan D. Hunter announced plans in January 2011 to introduce a bill designed to delay the end of DADT. His proposed legislation required all of the chiefs of the armed services to submit the certification at the time required only of the President, Defense Secretary and Joint Chiefs chairman.[161] In April, Perkins of the Family Research Council argued that the Pentagon was misrepresenting its own survey data and that hearings by the House Armed Services Committee, now under Republican control, could persuade Obama to withhold certification.[162] Congressional efforts to prevent the change in policy from going into effect continued into May and June 2011.[163]

On January 29, 2011, Pentagon officials stated that the training process to prepare troops for the end of DADT would begin in February and would proceed quickly, though they suggested that it might not be completed in 2011.[164] On the same day, the DOD announced it would not offer any additional compensation to service members who had been discharged under DADT, who received half of the separation pay other honorably discharged service members received.[165]

In May 2011, the U.S. Army reprimanded three colonels for performing a skit in March 2011 at a function at Yongsan Garrison, South Korea, that mocked the repeal.[166]

In May 2011, revelations that an April Navy memo relating to its DADT training guidelines contemplated allowing same-sex weddings in base chapels and allowing chaplains to officiate if they so chose resulted in a letter of protest from 63 Republican congressman, citing the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA) as controlling the use of federal property.[167] Tony Perkins of the Family Research Council said the guidelines "make it even more uncomfortable for men and women of faith to perform their duties".[168] A Pentagon spokesperson replied that DOMA "does not limit the type of religious ceremonies a chaplain may perform in a chapel on a military installation", and a Navy spokesperson said that "A chaplain can conduct a same-sex ceremony if it is in the tenets of his faith".[169] A few days later the Navy rescinded its earlier instructions "pending additional legal and policy review and interdepartmental coordination".[170]

While waiting for certification, several service members were discharged at their own insistence[71] until a July 6 ruling from a federal appeals court barred further enforcement of the U.S. military's ban on openly gay service members,[8] which the military promptly did.[171]

Anticipating the lifting of DADT, some active duty service members wearing civilian clothes marched in San Diego's gay pride parade on July 16. The DOD noted that participation "does not constitute a declaration of sexual orientation".[172]

President Obama, Secretary of Defense Leon Panetta, and Admiral Mike Mullen, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, sent the certification required by the Repeal Act to Congress on July 22, 2011, setting the end of DADT for September 20, 2011.[173] A Pentagon spokesman said that service members discharged under DADT would be able to re-apply to rejoin the military then.[174]

At the end of August 2011, the DOD approved the distribution of the magazine produced by OutServe, an organization of gay and lesbian service members, at Army and Air Force base exchanges beginning with the September 20 issue, coinciding with the end of DADT.[175]

On September 20, Air Force officials announced that 22 Air Force Instructions were "updated as a result of the repeal of DADT".[176] On September 30, 2011, the Department of Defense modified regulations to reflect the repeal by deleting "homosexual conduct" as a ground for administrative separation.[177][178]

Day of repeal and aftermath

[edit]

On the eve of repeal, US Air Force 1st Lt. Josh Seefried, one of the founders of OutServe, an organization of LGBT troops, revealed his identity after two years of hiding behind a pseudonym.[179] Senior Airman Randy Phillips, after conducting a social media campaign seeking encouragement coming out and already out to his military co-workers, came out to his father on the evening of September 19. When the video of their conversation he posted on YouTube went viral, it made him, in one journalist's estimation, "the poster boy for the DADT repeal".[180] The moment the repeal took effect at midnight on September 19, US Navy Lt. Gary C. Ross married his same-sex partner of eleven and a half years, Dan Swezy, making them the first same-sex military couple to legally marry in the United States.[181] Retired Rear Adm. Alan M. Steinman became the highest-ranking person to come out immediately following the end of DADT.[182] HBO produced a World of Wonder documentary, The Strange History of Don't Ask, Don't Tell, and premiered it on September 20. Variety called it "an unapologetic piece of liberal advocacy" and "a testament to what formidable opponents ignorance and prejudice can be".[183] Discharge proceedings on the grounds of homosexuality, some begun years earlier, came to an end.[184]

In the weeks that followed, a series of firsts attracted press attention to the impact of the repeal. The Marine Corps were the first branch of the armed services to recruit from the LGBTQ community.[185] Reservist Jeremy Johnson became the first person discharged under DADT to re-enlist.[186] Jase Daniels became the first to return to active duty, re-joining the Navy as a third class petty officer.[187] On December 2, Air Force intelligence officer Ginger Wallace became the first open LGBT service member to have a same-sex partner participate in the "pinning-on" ceremony that marked her promotion to colonel.[188] On December 23, after 80 days at sea, US Navy Petty Officer 2nd Class Marissa Gaeta won the right to the traditional "first kiss" upon returning to port and shared it with her same-sex partner.[189] On January 20, 2012, U.S. service members deployed to Bagram, Afghanistan, produced a video in support of the It Gets Better Project, which aims to support LGBT at-risk youth.[190] Widespread news coverage continued even months after the repeal date, when a photograph of Marine Sgt. Brandon Morgan kissing his partner at a February 22, 2012, homecoming celebration on Marine Corps Base Hawaii went viral.[191] When asked for a comment, a spokesperson for the Marine Corps said: "It's your typical homecoming photo."[192]

On September 30, 2011, Under Secretary of Defense Clifford Stanley announced the DOD's policy that military chaplains are allowed to perform same-sex marriages "on or off a military installation" where local law permits them. His memo noted that "a chaplain is not required to participate in or officiate a private ceremony if doing so would be in variance with the tenets of his or her religion" and "a military chaplain's participation in a private ceremony does not constitute an endorsement of the ceremony by DoD".[193] Some religious groups announced that their chaplains would not participate in such weddings, including an organization of evangelical Protestants, the Chaplain Alliance for Religious Liberty[194] and Roman Catholics led by Archbishop Timothy Broglio of the Archdiocese for the Military Services, USA.[195]

In late October 2011, speaking at the Air Force Academy, Colonel Gary Packard, leader of the team that drafted the DOD's repeal implementation plan, said: "The best quote I've heard so far is, 'Well, some people's Facebook status changed, but that was about it.'"[196] In late November, discussing the repeal of DADT and its implementation, Marine General James F. Amos said "I'm very pleased with how it has gone" and called it a "non-event". He said his earlier public opposition was appropriate based on ongoing combat operations and the negative assessment of the policy given by 56% of combat troops under his command in the Department of Defense's November 2010 survey. A Defense Department spokesperson said implementation of repeal occurred without incident and added: "We attribute this success to our comprehensive pre-repeal training program, combined with the continued close monitoring and enforcement of standards by our military leaders at all levels."[197]

In December 2011, Congress considered two DADT-related amendments in the course of work on the National Defense Authorization Act for 2012. The Senate approved 97–3, an amendment removing the prohibition on sodomy found in Article 125 of the Uniform Code of Military Justice as recommended by the Comprehensive Review Working Group (CRWG) a year earlier.[198][199] The House approved an amendment banning same-sex marriages from being performed at military bases or by military employees, including chaplains and other employees of the military when "acting in an official capacity". Neither amendment appeared in the final legislation.[198]

In July 2012, the Department of Defense granted permission for military personnel to wear their uniforms while participating in the San Diego Pride Parade. This was the first time that U.S. military personnel were permitted to wear their service uniforms in such a parade.[200]

Marking the first anniversary of the passage of the Repeal Act, television news networks reported no incidents in the three months since DADT ended. One aired video of a social gathering for gay service members at a base in Afghanistan.[201] Another reported on the experience of lesbian and gay troops, including some rejection after coming out to colleagues.[202]

The Palm Center, a think tank that studies issues of sexuality and the military, released a study in September 2012 that found no negative consequences, nor any effect on military effectiveness from DADT repeal. This study began six months following repeal and concluded at the one year mark. The study included surveys of 553 generals and admirals who had opposed repeal, experts who supported DADT, and more than 60 heterosexual, gay, lesbian and bisexual active duty service personnel.[203][204]

On January 7, 2013, the ACLU reached a settlement with the federal government in Collins v. United States. It provided for the payment of full separation pay to service members discharged under DADT since November 10, 2004, who had previously been granted only half that.[205]

2012 presidential campaign issue

[edit]Several candidates for the 2012 Republican presidential nomination called for the restoration of DADT, including Michele Bachmann,[206] Rick Perry,[207] and Rick Santorum.[208] Newt Gingrich called for an extensive review of DADT's repeal.[209]

Ron Paul, having voted for the Repeal Act, maintained his support for allowing military service by open homosexuals.[210] Herman Cain called the issue "a distraction" and opposed reinstating DADT.[211] Mitt Romney said that the winding down of military operations in Iraq and Afghanistan obviated his opposition to the repeal and said he was not proposing any change to policy.[212]

On September 22, 2011, the audience at a Republican candidates' debate booed a U.S. soldier posted in Iraq who asked a question via video about the repeal of DADT, and none of the candidates acknowledged or responded to the crowd's behavior.[213] Two days later, Obama commented on the incident while addressing a dinner of the Human Rights Campaign: "You want to be commander in chief? You can start by standing up for the men and women who wear the uniform of the United States, even when it's not politically convenient".[214]

In June 2012, Rep. Howard McKeon, Republican chair of the House Armed Services Committee, said he considered the repeal of DADT a settled issue, and that if Romney became president he would not advocate its reinstatement, though others in his party might.[215]

2021 benefits restoration

[edit]In September 2021, on the 10th anniversary of the Don't Ask, Don't Tell repeal, President Joe Biden announced that the Veterans Administration would start providing benefits for service members who received other-than-honorable discharges (before DADT was enacted and while it was in effect) because of their sexual orientation.[216]

In 2024, more than 800 veterans who had been previously dishonorably discharged under DADT had their cases reviewed and discharge papers automatically updated to honorable discharge status. With this review, nearly all of the 13,500 people who were dishonorably discharged under DADT now have an honorable discharge and as a result, can access benefits for veterans.[217]

Views of the policy

[edit]Public opinion

[edit]

In 1993, Time reported that 44% of those polled supported openly gay service members,[218] and in 1994, a CNN poll indicated 53% of Americans believed gays and lesbians should be permitted to serve openly.[219]

According to a December 2010 Washington Post–ABC News poll, 77% of Americans said gays and lesbians who publicly disclose their sexual orientation should be able to serve in the military. That number showed little change from polls over the previous two years, but represented the highest level of support in a Post-ABC poll. The support also cut across partisan and ideological lines, with majorities of Democrats (86%), Republicans (74%), independents (74%), liberals (92%), conservatives (67%), white evangelical Protestants (70%) and non-religious (84%) in favor of homosexuals serving openly.[220]

A November 2010 survey by the Pew Research Center found that 58% of the U.S. public favored allowing gays and lesbians to serve openly in the military, while less than half as many (27%) were opposed.[221] According to a November 2010 CNN/Opinion Research Corporation poll, 72% of adult Americans favored permitting people who are openly gay or lesbian to serve in the military, while 23% opposed it.[222] "The main difference between the CNN poll and the Pew poll is in the number of respondents who told pollsters that they didn't have an opinion on this topic – 16 percent in the Pew poll compared to only five percent in the CNN survey", said CNN Polling Director Keating Holland. "The two polls report virtually the same number who say they oppose gays serving openly in the military, which suggests that there are some people who favor that change in policy but for some reason were reluctant to admit that to the Pew interviewers. That happens occasionally on topics where moral issues and equal-treatment issues intersect."[223]

A February 2010 Quinnipiac University Polling Institute national poll showed 57% of American voters favored gays serving openly, compared to 36% opposed, while 66% said not allowing openly gay personnel to serve is discrimination, compared to 31% who did not see it as discrimination.[224] A CBS News/New York Times national poll done at the same time showed 58% of Americans favored gays serving openly, compared to 28% opposed.[225]

Chaplains and religious groups

[edit]Chaplain groups and religious organizations took various positions on DADT. Some felt that the policy needed to be withdrawn to make the military more inclusive. The Southern Baptist Convention battled the repeal of DADT, warning that their endorsements for chaplains might be withdrawn if the repeal took place.[226][227] They took the position that allowing gay men and women to serve in the military without restriction would have a negative impact on the ability of chaplains who think homosexuality is a sin to speak freely regarding their religious beliefs. The Roman Catholic Church called for the retention of the policy, but had no plans to withdraw its priests from serving as military chaplains.[228] Sixty-five retired chaplains signed a letter opposing repeal, stating that repeal would make it impossible for chaplains whose faith teaches that same-sex behavior is immoral to minister to military service members.[229] Other religious organizations and agencies called the repeal of the policy a "non-event" or "non-issue" for chaplains, saying that chaplains have always supported military service personnel, whether or not they agree with all their actions or beliefs.[230][231][232]

Discharges under DADT

[edit]After the policy was introduced in 1993, the military discharged over 13,000 troops from the military under DADT.[111][233][234] The number of discharges per fiscal year under DADT dropped sharply after the September 11 attacks and remained comparatively low through to the repeal. Discharges exceeded 600 every year until 2009.

| Year | Coast Guard | Marines | Navy | Army | Air Force | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1994[235] | 0 | 36 | 258 | 136 | 187 | 617 |

| 1995[235] | 15 | 69 | 269 | 184 | 235 | 772 |

| 1996[235] | 12 | 60 | 315 | 199 | 284 | 870 |

| 1997[235] | 10 | 78 | 413 | 197 | 309 | 1,007 |

| 1998[235] | 14 | 77 | 345 | 312 | 415 | 1,163 |

| 1999[235] | 12 | 97 | 314 | 271 | 352 | 1,046 |

| 2000[235][236] | 19 | 114 | 358 | 573 | 177 | 1,241 |

| 2001[235][236] | 14 | 115 | 314 | 638 | 217 | 1,273 |

| 2002[235][236] | 29 | 109 | 218 | 429 | 121 | 906 |

| 2003[235] | – | – | – | – | – | 787 |

| 2004[237] | 15 | 59 | 177 | 325 | 92 | 668 |

| 2005[237] | 16 | 75 | 177 | 386 | 88 | 742 |

| 2006[235] | – | – | – | – | – | 623 |

| 2007[235] | – | – | – | – | – | 627 |

| 2008[238] | – | – | – | – | – | 619 |

| 2009 | – | – | – | – | – | 428 |

| 2010[239] | 11 | – | – | – | – | 261 |

| Total | ≥156 | ≥889 | ≥3,158 | ≥3,650 | ≥2,477 | 13,650 |

| Disclaimer: These statistics are not official and only include soldiers who came forward to the Servicemembers Legal Defense Network. Because some soldiers do not disclose their discharge, some of the numbers may be inaccurate. | ||||||

-

Rear Adm. Vic Guillory, commander of U.S. Naval Forces Southern Command and U.S. 4th Fleet leads DADT repeal training for Tier 2 command leadership at Naval Station Mayport, March 17, 2011

-

Naval Special Warfare Command personnel watching Chief of Naval Operations Adm. Gary Roughead during DADT repeal training, April 6, 2011

-

DADT Repeal training for enlisted, officer and civilian staff at Naval Medical Center San Diego, May 5, 2011

State-based gay and lesbian military veteran laws

[edit]In November 2019, both Rhode Island and New York State signed into law and implemented restoring military benefits to gay and lesbian military veterans. It is estimated that approximately 100,000 individuals were discharged between the beginning of World War II and the repeal of the Don't Ask Don't Tell policy in September 2011.[240]

See also

[edit]- Liberal homophobia

- Steve May, gay Republican Arizona legislator, Army reservist until May 2001

- Sexual orientation and gender identity in the United States military

- Sexual orientation and military service – for information on policies in military services worldwide

- Transgender military ban in the United States

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ "Department of Defense Directive 1304.26". Retrieved September 11, 2013.

- ^ "Gays in the Military". Retrieved September 11, 2013.

- ^

- ^ 10 U.S.C. § 654(e)

- ^ "Army Regulation 40-501, Standards of Medical Fitness, Chapters 2-27n and 3–35" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on February 1, 2017. Retrieved December 21, 2013.

- ^ "The Legal Brief "Don't Ask, Don't Tell, Don't Pursue, Don't Harass: Reference (a): Personnel Manual, COMDTINST M1000.6, Ch. 12.E"" (PDF). United States Coast Guard Ninth District Legal Office. May 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 29, 2011. Retrieved October 23, 2010.

- ^ a b Sheryl Gay Stolberg (December 22, 2010). "Obama Signs Away 'Don't Ask, Don't Tell'". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 1, 2022. Retrieved December 22, 2010.

- ^ a b "In reversal, federal court orders immediate end to 'don't ask, don't tell' policy". The Washington Post. Associated Press. July 6, 2011. Archived from the original on December 6, 2018. Retrieved July 6, 2011.

- ^ "Obama certifies end of military's gay ban". NBC News. Reuters. July 22, 2011. Retrieved July 22, 2011.

- ^ "Extending Benefits to Same-Sex Domestic Partners of Military Members" (PDF). U.S. Army. February 11, 2013. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 21, 2022.

- ^ "DD Form X653". reginfo.gov. August 20, 2013.

- ^ "DoD Announces Extension of Equal Benefits for Same-Sex Military Spouses". AMPA The American Military Partner Association. August 14, 2013.

- ^ Bérubé, Coming Out Under Fire, 9–14, 19

- ^ Bérubé, Coming Out Under Fire, 142–3

- ^ Jones, p. 3

- ^ E. Lawrence Gibson, Get Off my Ship : Ensign Berg vs. the U.S. Navy (NY: Avon, 1978), 256–67

- ^ Lillian Faderman (1991). Odd Girls and Twilight Lovers: A History of Lesbian Life in Twentieth-Century America. New York: Penguin. p. 155. ISBN 978-0-14-017122-8.

- ^ Lillian Faderman (1991). Odd Girls and Twilight Lovers: A History of Lesbian Life in Twentieth-Century America. New York: Penguin. pp. 119–138. ISBN 978-0-14-017122-8.

- ^ "The Sexes: The Sergeant v. the Air Force". Time. September 8, 1975. Retrieved July 26, 2011. Other prominent cases included Copy Berg, Stephen Donaldson.

- ^ Fordham University: "Homosexuals in the Armed Forces: United States GAO Report", June 12, 1992. Retrieved February 27, 2012.

- ^ Vaid, Virtual Equality, 155-8

- ^ Nathaniel Frank, Unfriendly Fire: How the Gay Ban Undermines the Military and Weakens America (NY: St. Martin's Press, 2009), 118–20; McFeeley, "Getting It Straight", 237-8

- ^ McFeeley, "Getting It Straight", 238

- ^ Stephen F. Hayes, Cheney: The Untold Story of America's Most Powerful and Controversial Vice President (NY: HarperCollins, 2007), 256

- ^ Brian P. Mitchell, Women in the military: Flirting with Disaster (Washington: Regnery Publishing, 1998), 281

- ^ McFeeley, "Getting It Straight", 237; Vaid, Virtual Equality, 158-9

- ^ Schmalz, Jeffrey (August 20, 1992). "The Gay Vote; Gay Rights and AIDS Emerging As Divisive Issues in Campaign", The New York Times. Retrieved February 27, 2012. See also: Schmitt, Eric (August 26, 1992). "Marine Corps Chaplain Says Homosexuals Threaten Military", The New York Times: Retrieved February 27, 2012

- ^ Vaid, Virtual Equality, 160

- ^ McFeeley, "Getting It Straight", 239

- ^ Schmitt, Eric (August 26, 1992). "Marine Corps Chaplain Says Homosexuals Threaten Military". The New York Times. Retrieved January 23, 2013.

- ^ Reza, H.G. (January 9, 1993). "Homosexual Sailor Beaten to Death, Navy Confirms", Los Angeles Times. Retrieved February 14, 2012.

- ^ a b Shankar, Thom (November 30, 2007). "A New Push to Roll Back 'Don't Ask, Don't Tell'". The New York Times. Retrieved December 29, 2012.

- ^ Schmitt, Eric (January 27, 1993). "Military Cites Wide Range of Reasons for Its Gay Ban". The New York Times. Retrieved June 9, 2011.

- ^ National Defense Research Institute; Rand Corporation Rand Corporation (1993). Sexual orientation and U.S. military personnel policy: options and assessment. Santa Monica, Calif: Rand. p. 406. ISBN 978-0-8330-1441-2.

- ^ Gregory M. Herek: Oral Statement of Gregory M. Herek, PhD to the House Armed Services Committee Archived September 27, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved February 24, 2012. The professional groups were the American Psychological Association, the American Psychiatric Association, the National Association of Social Workers, the American Counseling Association, the American Nursing Association, and the Sexuality Information and Education Council of the United States.

- ^ "Major General Barry M. Goldwater". US Air Force. Archived from the original on March 31, 2013.

- ^ The Advocate. Here Publishing. July 7, 1998. p. 15.

- ^ "David Mixner, LGBTQ+ activist and Bill Clinton campaign adviser, dies at 77". Associated Press. March 12, 2024. Retrieved March 12, 2024.

- ^ a b "Lesbians and Gay Men in the U.S. Military: Historical Background". Psychology UC Davis. Retrieved March 16, 2021.

- ^ a b c "Don't Ask Don't Tell Don't Pursue". Robert Crown Law Library. September 7, 1999. Archived from the original on April 25, 2012.

- ^ "Defense Directive 1304.26: Qualification Standards for Enlistment, Appointment, and Induction". Department of Defense. December 21, 1993.

- ^ "DoDD 1332.14, December 21, 1993". Stanford University. Archived from the original on July 4, 2010. Retrieved December 19, 2010.

- ^ "Title 10, Subtitle A, Part II, Chapter 37, § 654. Policy concerning homosexuality in the armed forces". Cornell Law School. June 9, 2010. Retrieved December 19, 2010.

- ^ Chuck Stewart (2001). Homosexuality and the law: a dictionary. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO. pp. 196–7. ISBN 978-1-57607-267-7.

- ^ The New York Times: Eric Schmitt, "U.S. Agencies Split over Legal Tactics on Gay Troop Plan", December 19, 1993. Retrieved April 7, 2012.

- ^ Richenberg v. Perry, 97 F.3d 256 (8th Cir. 1996); Thomasson v. Perry, 80 F.3d 915 (4th Cir. 1996); Able v. United States, 155 F.3d 628 (2d Cir. 1998); Cook v. Gates, 528 F.3d 42 (1st Cir. 2008); Holmes v. California National Guard, 124 F.3d 1126 (9th Cir. 1998)

- ^ Mears, Bill (2006). "Justices uphold military recruiting on campuses". CNN. Retrieved March 6, 2006.

- ^ Sporkin, Stanley (January 26, 1998). "Memorandum Opinion, Timothy R. McVeigh v. William S. Cohen, et al." (PDF). U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 1, 2011. Retrieved September 21, 2014.

- ^ Rich, Frank (January 17, 1998). "The 2 Tim McVeighs". The New York Times. Retrieved September 21, 2014.

- ^ Shenon, Philip (June 12, 1998). "Sailor Victorious in Gay Case of On-Line Privacy". The New York Times. Retrieved September 21, 2014.

- ^ Bravin, Jess; Laura Meckler (May 19, 2009). "Obama Avoids Test on Gays in Military". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved July 24, 2010.

- ^ Johnson, Gene (September 24, 2010). "Judge orders lesbian reinstated to Air Force – Case challenges 'Don't ask, don't tell' policy". NBC News. Associated Press. Retrieved September 24, 2010.

- ^ "DOJ Appeals Lesbian's Reinstatement to Air Force". CBS News. November 24, 2010. Archived from the original on January 19, 2013. Retrieved December 29, 2012.

- ^ Seattle Post Intelligencer: Pulkkinnen, Levi (May 10, 2011). "Pentagon settles with McChord major fired for being lesbian". Retrieved May 12, 2011

- ^ Garcia, Michelle (July 22, 2010). "Key DADT Repeal Advocate Testifies". Advocate.com. Archived from the original on July 24, 2010. Retrieved July 22, 2010.

- ^ Law.com: Constitutional Challenge to 'Don't Ask, Don't Tell' Reaches Trial

- ^ "In the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit" (PDF). March 28, 2011. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 27, 2016. Retrieved March 16, 2021.

- ^ "US judge: 'Don't ask, don't tell' unconstitutional". Associated Press. September 10, 2010. Archived from the original on September 13, 2010.

- ^ Phil Willon (September 9, 2010). "Judge declares U.S. military's 'don't ask, don't tell' policy openly banning gay service members unconstitutional". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ "Judge orders military to stop enforcing don't ask, don't tell". CNN. October 12, 2010. Archived from the original on February 24, 2021. Retrieved October 13, 2010.

- ^ Schwartz, John (October 12, 2010). "Judge Orders U.S. Military to Stop 'Don't Ask, Don't Tell'". The New York Times. Retrieved December 29, 2012.

- ^ "Justice department seeks stay of judge's 'don't-ask-don't-tell' ruling". CNN. October 15, 2010.

- ^ "Appeals court delays injunction against 'don't ask, don't tell'". CNN. October 19, 2010. Retrieved October 23, 2010.

- ^ "'Don't ask, don't tell' back in force after appeals court issues stay". The Christian Science Monitor. October 21, 2010.

- ^ John Schwartz (November 1, 2010). "Military Policy on Gays to Stand, Pending Appeal". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 1, 2022. Retrieved November 3, 2010.

- ^ Ed O'Keefe (November 6, 2010). "Group asks high court to lift 'don't ask' ban". The Washington Post. Retrieved November 9, 2010.

- ^ "Military recruiters told they can accept openly gay applicants". CNN. October 19, 2010.

- ^ ""Don't ask, don't tell" no longer enforced, Dan Choi reenlists". Salon.

- ^ The Advocate: "DADT Case Still Alive" Archived February 2, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, January 30, 2011. Retrieved February 14, 2012.

- ^ "'Don't Ask, Don't Tell' End Urged By Lawyers For Log Cabin Republicans". Huffington Post. March 28, 2011.

- ^ a b Harmon, Andrew (June 27, 2011). "Pentagon Confirms New DADT Discharges". The Advocate. Retrieved July 6, 2011.

- ^ "Appeals court orders immediate halt to gay military ban". MSNBC. July 6, 2011. Retrieved December 29, 2012.

- ^ "9th Circuit orders gov't to state position on DADT". San Diego Union Tribune. July 11, 2011. Retrieved December 29, 2012.

- ^ a b Mohajer, Shaya Tayefe (July 15, 2011). "Court: 'don't ask, don't tell' will stay in place". ABC News. Associated Press. Retrieved March 16, 2021.

- ^ Gerstein, Josh (September 29, 2011). "Appeals court nullifies 'don't ask, don't tell' ruling". The Politico. Retrieved September 29, 2011.

- ^ a b David F. Burrelli (February 2010). Homosexuals and the U. S. Military: Current Issues. DIANE Publishing. p. 20. ISBN 978-1-4379-2329-2.

- ^ National Archives: Executive Order 13140, October 6, 1999. Retrieved March 16, 2012.

- ^ CNN: "Pentagon to review don't ask, don't tell policy", December 13, 1999. Retrieved March 16, 2012.

- ^ Nagourney, Adam (December 9, 1999). "Hillary Clinton Faults Policy Of 'Don't Ask'". The New York Times. Retrieved January 1, 2013.

- ^ Mundy, Carl E. (December 20, 1999). "'Don't Ask' Policy: Don't Call It A Failure". Philadelphia Inquirer. Archived from the original on January 7, 2012. Retrieved December 30, 2012.

- ^ Schmitt, Eric (December 25, 1999). "Gay Rights Advocates Plan to Press Clinton to Undo Policy of 'Don't Ask, Don't Tell'". The New York Times. Retrieved January 11, 2013.

- ^ The New York Times: Steven Lee Myers, "Officers Riled by Policy on Gays Proposed in Gore-Bradley Debate", January 7, 2000. Retrieved April 8, 2012.

- ^ American Presidency Project: Democratic Party Platform of 2000, August 14, 2000. Retrieved December 27, 2012.

- ^ American Presidency Project: Republican Party Platform of 2000, July 31, 2000. Retrieved December 27, 2012.

- ^ ABC News: Julia Campbell, "Bush on Gay Rights Issues", January 17, 2001. Retrieved April 4, 2012.

- ^ Singer, Lt Col Charles McLean and Peter W. (May 27, 2010). "Don't Make a Big Deal of Ending Don't Ask Don't Tell: Lessons from U.S. Military Allies on Allowing Homosexuals to Serve". Brookings. Retrieved February 27, 2019.

- ^ The Advocate. Here Publishing. March 30, 2004.

- ^ American Psychological Association: Proceedings of the American Psychological Association for the legislative year 2004. Minutes of the meeting of the Council of Representatives July 28 & 30, 2004, Honolulu, Hawaii. Retrieved March 5, 2012.

- ^ American Presidency Project: Republican Party Platform of 2004, August 30, 2004. Retrieved December 27, 2012.